Apple’s Ad Network Gets ‘Preferential Access To Users’ Data’ vs Facebook, Google, Others – Forbes

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

SOURCE: John Koetsier | Forbes

Is Apple playing fair?

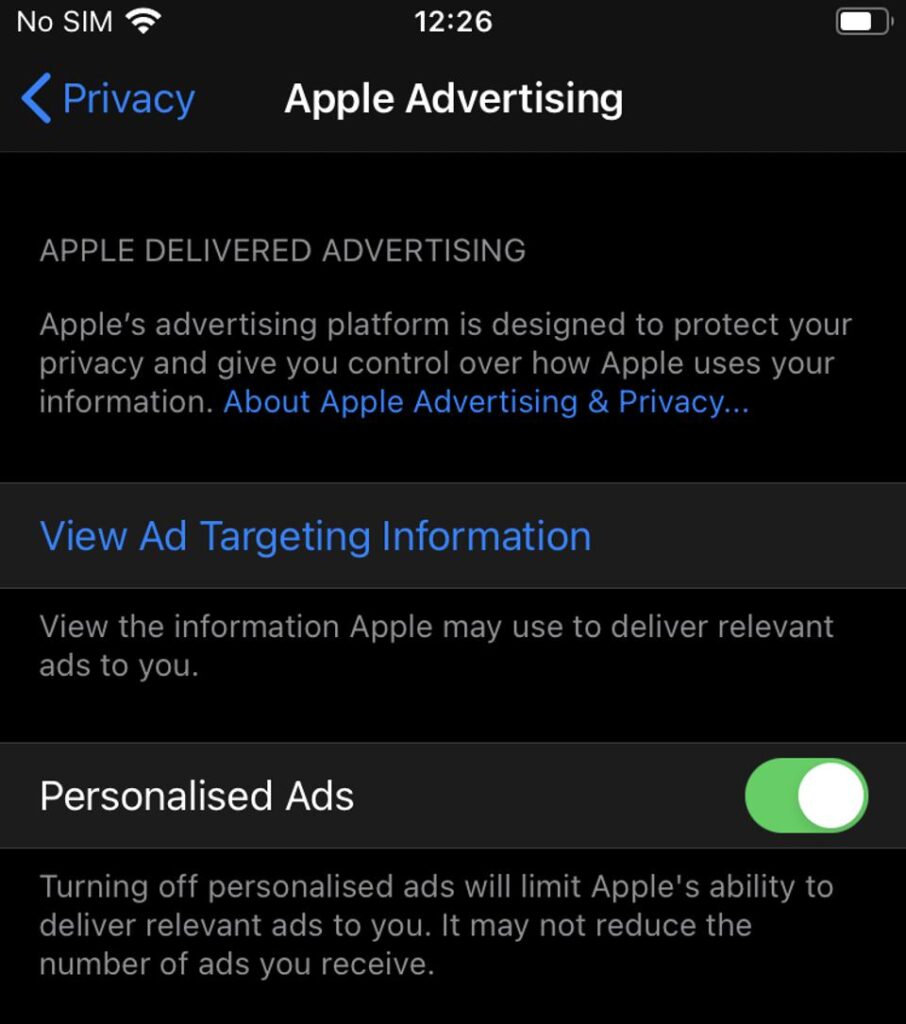

Apple looks to be giving its own ad network a leg up on competitors with customer data that other ad networks can’t access. In iOS 14, Apple Advertising appears to have a separate settings panel with a default-on setting. Other advertisers and ad networks on iOS, however, need to ask permission every single time.

“It’s preferential access to users’ data,” mobile expert Eric Seufert says. “Now they’re best-positioned to gain market share in mobile app install ads.”

That’s close to an $80 billion industry that Google and Facebook currently dominate.

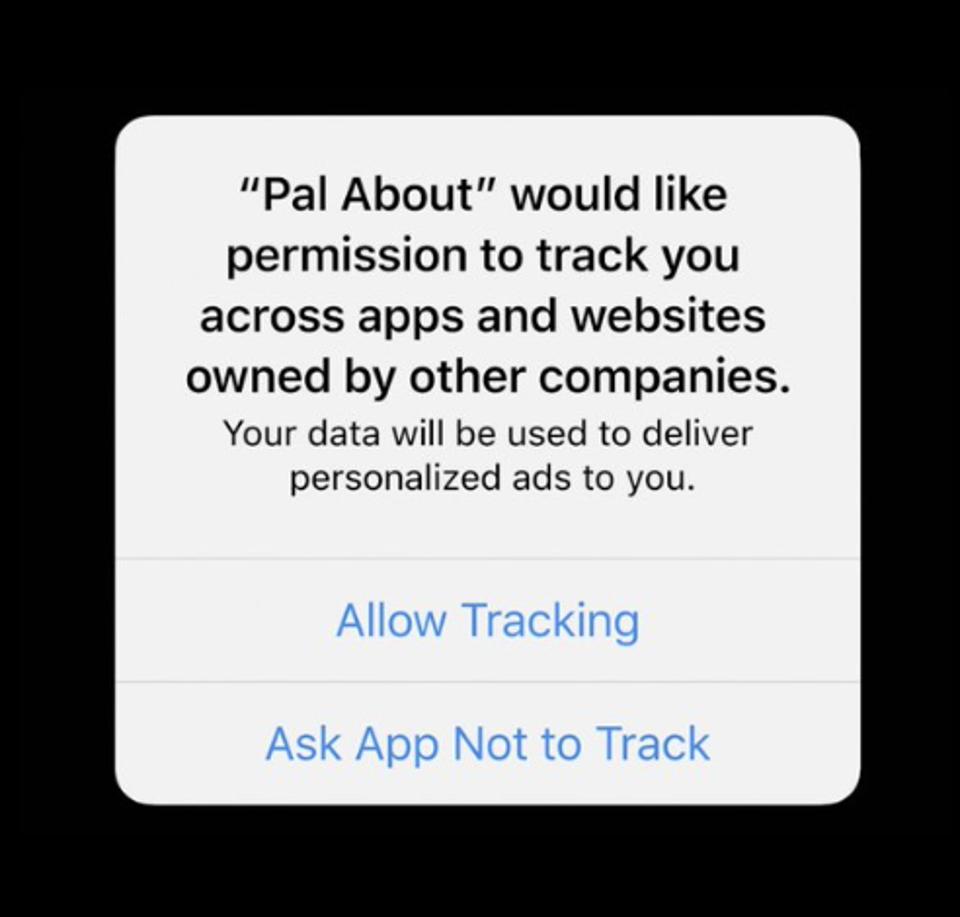

Apple’s making a major user privacy change in the next version of its mobile operating system. Mobile advertisers will no longer be able to monitor the results of their advertising on a granular per-device basis by default, because Apple crippled its own identifier for advertisers, the IDFA. Essentially, Apple is forcing advertisers to use a per-app permission pop-up with scary language, telling users the app wants permission to track them across other apps and websites.

In contrast, Apple’s own advertising service looks to enable personalization by default, giving it a platform-level advantage over competitors.

Apple’s preferences pane for Apple Advertising, or Apple Search Ads, in iOS 14. Other

apps have to access different functionalities in a tracking-specific section.

And those competitors aren’t just tiny ad networks. They include Apple’s corporate rivals such as Google and Facebook.

The mobile marketing ecosystem is complex, but essentially, advertisers and ad networks use the IDFA to measure the results of their marketing. They can stop showing you ads if you don’t click on them, connect an ad you saw to an app you installed, and more. People can turn off the IDFA, but only about 30% actually do. The IDFA replaced more dangerous and privacy-exposing device identifiers that people could not turn off, but there are still things that bad actors could use the IDFA for that could result in long-term privacy problems: tracking people, monitoring everything they do, and building up profiles of their activity.

In fact, a source told me that a Chinese national who worked for Machine Zone, a major game studio that produces games like Mobile Strike, Game of War, and Final Fantasy, attempted to steal hundreds of thousands of IDFA records. Jing Zeng was arrested by the FBI literally on an airplane about to take off for China, holding in his possession a USB thumb drive filled with IDFAs.

That could be simply corporate espionage — stealing the identifiers for all the highest-value players in a game — but it could also extend to national security, with data on which apps high-leverage individuals use.

Knowing, for instance, that a politician uses Grindr could be used against him.

And while the IDFA is not tied to a person by a device, it’s well-known that in many cases, you can be easily identified via ostensibly “anonymized data.”

To improve user privacy — and likely out of a concern for Cambridge Analytica-like exposure in a potential major publicized breach — Apple decided to make the IDFA opt in rather than opt out in iOS 14.

Think GDPR notifications — this website uses cookies, do you accept — every time you install an app. But notice the significantly scarier language: “’Pal About’ would like permission to track you across apps and websites owned by other companies.”

The new user permission dialog in iOS 14 from Apple that allows or denies advertiser

access to the IDFA (identifier for advertisers).

This is language that is likely designed to minimize opt-in.

Contrast it with the language that Apple uses in its much harder-to-find separate settings pane for Apple Advertising. Apple’s ad network gets to use very friendly language, such as “designed to protect your privacy” and “give you control.”

The result, most mobile experts think, will be a below-20% opt-in rate for IDFA tracking. (That’s probably high.)

This is good for privacy.

It’s also bad for legitimate advertisers and marketers.

But potentially worse is Apple retaining advantages that other ecosystem players cannot, simply because Apple owns the iOS platform. Everyone else needs permission to allow “tracking,” but Apple retains its access to more data. And Apple potentially has a lot of on-device data. While the company is privacy-centric, and it does mix your data with groups of 5,000 other people to only target large segments, not individuals, Apple explicitly says it uses data about “your devices’ connectivity, time setting, type, language, and location” to personalize ads to you.

Apple also uses data gathered during your searches on the App Store and the articles you read in Apple News, plus your mobile carrier.

“They obviously have some kind of targeting that goes to device level,” Seufert says. “Some of that might be contextual, but regardless, it’s preferential access. This is kind of shocking … it’s just so brazen.”

Those capabilities are not exposed to others.

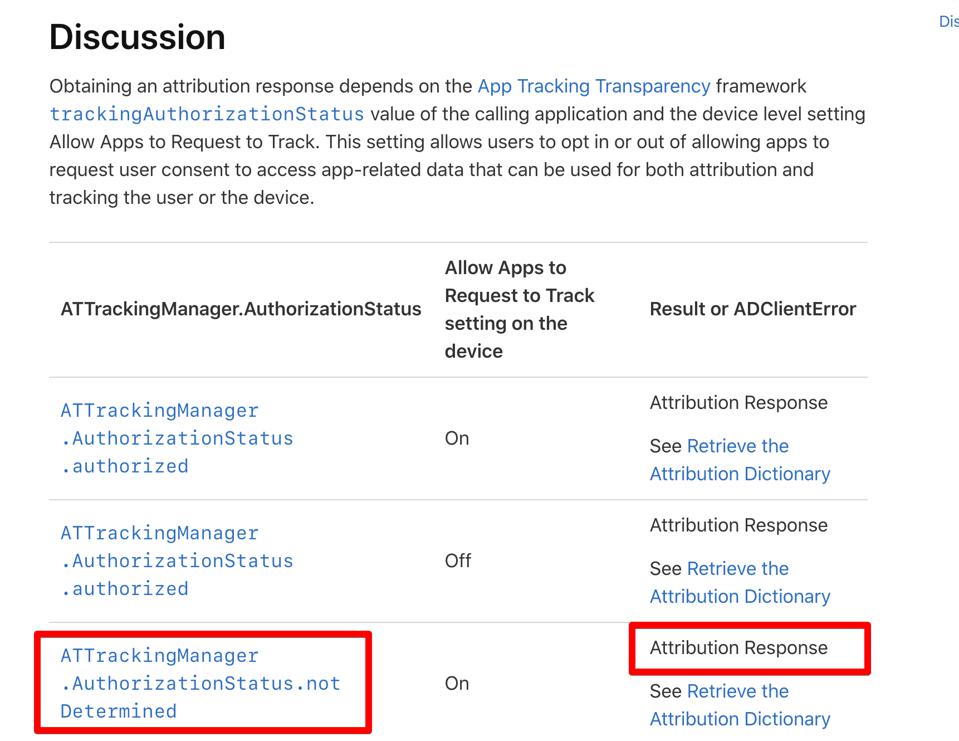

And in fact Apple Advertising retains those capabilities even if someone does not assent to tracking, as its own iAd documentation reveals (Apple variously calls its ad network Apple Search Ads, Apple Advertising, and its original name, iAd).

A screenshot of Apple’s advertising documentation, showing that attribution is on

even when a user’s IDFA status has not been explicitly set.

In the first scenario for Apple Advertising attribution (attribution is tracking to determine the results of a user viewing an ad) the user has allowed the use of her IDFA, and attribution happens, a mobile expert told me. In the second scenario, a user clicks “no, don’t track me,” and no attribution happens.

In the third scenario, the user was never asked, but Apple Advertising can still run targeting and attribution.

That’s a capability no other ad network can possess, because essentially it’s the iOS 13 means of advertising attribution where assent is assumed unless explicitly revoked. Other ad networks cannot assume assent and do not get the IDFA without explicitly requesting it and a user granting it. That means Google, Facebook, AdColony, Vungle, IronSource, or any other ad network now has less data for ad targeting and ad delivery optimization than Apple.

And that’s an advantage simply based on who owns a platform.

Which, one would think, could have antitrust implications.

It’s possible that this is a temporary situation. One source in the mobile marketing industry who requested anonymity said that Apple is using an “archaic” attribution engine they built years ago, and they are currently upgrading their code to comply with the new rules. The thinking is that Apple Advertising will eventually be compatible with SKAdNetwork, a framework Apple built for advertisers. SKAdNetwork enables completely privacy-safe advertising attribution, meaning that brands can know which ad campaigns worked, but they won’t have specific, granular data on which people viewed an ad, clicked an ad, or took action.

There remain two issues, however.

First, Apple’s imposing a September deadline on the entire advertising industry, including Google and Facebook, for IDFA compliance. When iOS 14 launches, the old world dies; the new world becomes reality. Apple appears to be giving its own ad network something of a grace period here, grandfathering Apple Advertising in.

That’s hardly fair.

The second issue is that it’s not clear that Apple Advertising will follow all the rules that Apple is forcing every other advertiser and ad network to follow. Who will police this, and how will anyone enforce consistency on Apple’s own platform? If Apple Advertising does not end up following the same rules as everyone else, that’s a long-term platform-based advantage against every other player in the space.

It’s possible to argue that Apple is privacy-focused and that it will not abuse the data it has access to. That’s likely true, though some will beg to differ, but it’s also besides the point. The entire issue in Apple’s multiple ongoing antitrust investigations is whether there’s a level playing field between Apple and its competitors on a platform that Apple built and grew to global proportions.

And that’s the true danger here for Apple.

That for the sake of a few billion dollars in revenue from Apple Advertising, it’s putting a trillion-dollar organization at risk.

This does not seem to be a wise bet.

In addition, Apple risks its IDFA deprecation being seen not so much as a privacy-enhancing move made out of altruistic goodwill as a competitive strategy to improve its positioning against massive rivals.