More people turning away from news, report says – BBC

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

SOURCE: Noor Nanji | BBC

More people are turning away from news, describing it as depressing, relentless and boring, a global study suggests.

Almost four in 10 (39%) people worldwide said they sometimes or often actively avoid the news, compared with 29% in 2017, according to the report by Oxford University’s Reuters Institute.

Wars in Ukraine and the Middle East may have contributed to people’s desire to switch off the news, the report’s authors said.

It said that news avoidance is now at record high levels.

A total of 94,943 adults across 47 countries were surveyed by YouGov in January and February for this year’s Digital News Report.

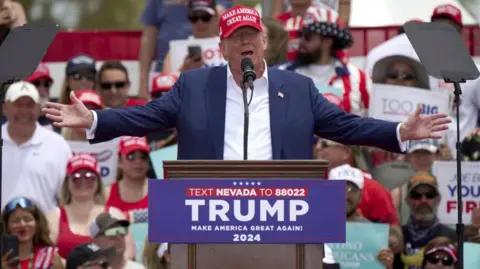

It comes at a time when billions of people around the world have been going to the polls in national and regional elections.

The report found that elections have increased interest in the news in a few countries, including the United States.

However, the overall trend remains firmly downwards, according to the study.

Around the world, 46% of people said they were very or extremely interested in the news – down from 63% in 2017.

In the UK, interest in news has almost halved since 2015.

“The news agenda has obviously been particularly difficult in recent years,” the report’s lead author Nic Newman told BBC News.

“You’ve had the pandemic [and] wars, so it’s a fairly natural reaction for people to turn away from the news, whether it’s to protect their mental health or simply wanting to get on with the rest of their lives.”

.

Mr Newman said those choosing to selectively avoid the news also often do so because they feel “powerless”.

“These are people who feel they have no agency over massive things that are happening in the world,” he said.

Some people feel increasingly overwhelmed and confused by the amount of news around, while others feel fatigued by politics, he added.

Women and younger people were more likely to feel worn out by the amount of news around, according to the report.

Meanwhile, trust in the news remains steady at 40%, but is still 4% lower overall than it was at the height of the Coronavirus pandemic, the survey suggested.

In the UK, trust in the news ticked up slightly this year, at 36%, but remains around 15 percentage points lower than before the Brexit referendum in 2016.

The BBC was the most trusted news brand in the UK, of the brands surveyed, followed by Channel 4 and ITV.

TikTok overtakes Twitter

The report found that audiences for traditional news sources like TV and print have fallen sharply over the past decade, with younger people preferring to get their news online or via social media.

In the UK, almost three-quarters of people (73%) said they get their news online, compared with 50% for TV and just 14% for print.

The most important social media platform for news is still Facebook, although it is in long-term decline.

YouTube and WhatsApp remain important news sources for many, while TikTok is on the rise and has now overtaken X (formerly Twitter) for the first time.

Thirteen percent of people use the video-sharing app for news, compared with 10% who use X.

The figure for TikTok is even higher for 18-24 year-olds globally, at 23%.

.

Linked to these shifts, video is becoming a more important source of online news, especially with younger groups.

Short news videos have the most appeal, according to the report.

“Consumers are adopting video because it is easy to use, and provides a wide range of relevant and engaging content,” Mr Newman said.

“But many traditional newsrooms are still rooted in a text-based culture and are struggling to adapt their storytelling.”

The report said that, for publishers, news podcasting is a bright spot.

But it is a “minority activity overall”, attracting primarily well-educated audiences.

Meanwhile, for journalists – some good news.

The report found widespread public suspicion about how artificial intelligence (AI) might be used in reporting, especially for hard news stories such as politics or war.

“There is more comfort with the use of AI in behind-the-scenes tasks such as transcription and translation; in supporting rather than replacing journalists,” it added.

This article was originally published on BBC – navigate to the original article here.