The story of Sony: from repair shop to revolution, how Walkman inventor changed music listening and, with PlayStation, home entertainment – South China Morning Post

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

SOURCE: Julian Ryall | South China Morning Post

Malia Verniolle was almost eight years old when her father gave her a gadget she says changed her life in a number of ways. She also recalls that the earliest incarnation of the Sony Walkman had a nasty habit of trapping her fingers in its spring-loaded door for cassette tapes.

“My father gave it to me as a joint present for Christmas and my birthday, which is in early January,” said Verniolle, who grew up and still lives in southern France. “I remember being stunned and delighted to receive what became a true companion. I was an only child and spent a lot of time on my own, so I took my Walkman with me everywhere I went.

“As soon as I put the headphones on, whether I was at home or simply walking in familiar places, music made everything seem special.”

She was wasn’t the only one to feel that way. Between the release of the first Sony Walkman on July 1, 1979 and the final cassette tape version rolling off the production line in October 2010, more than 385 million units were sold.

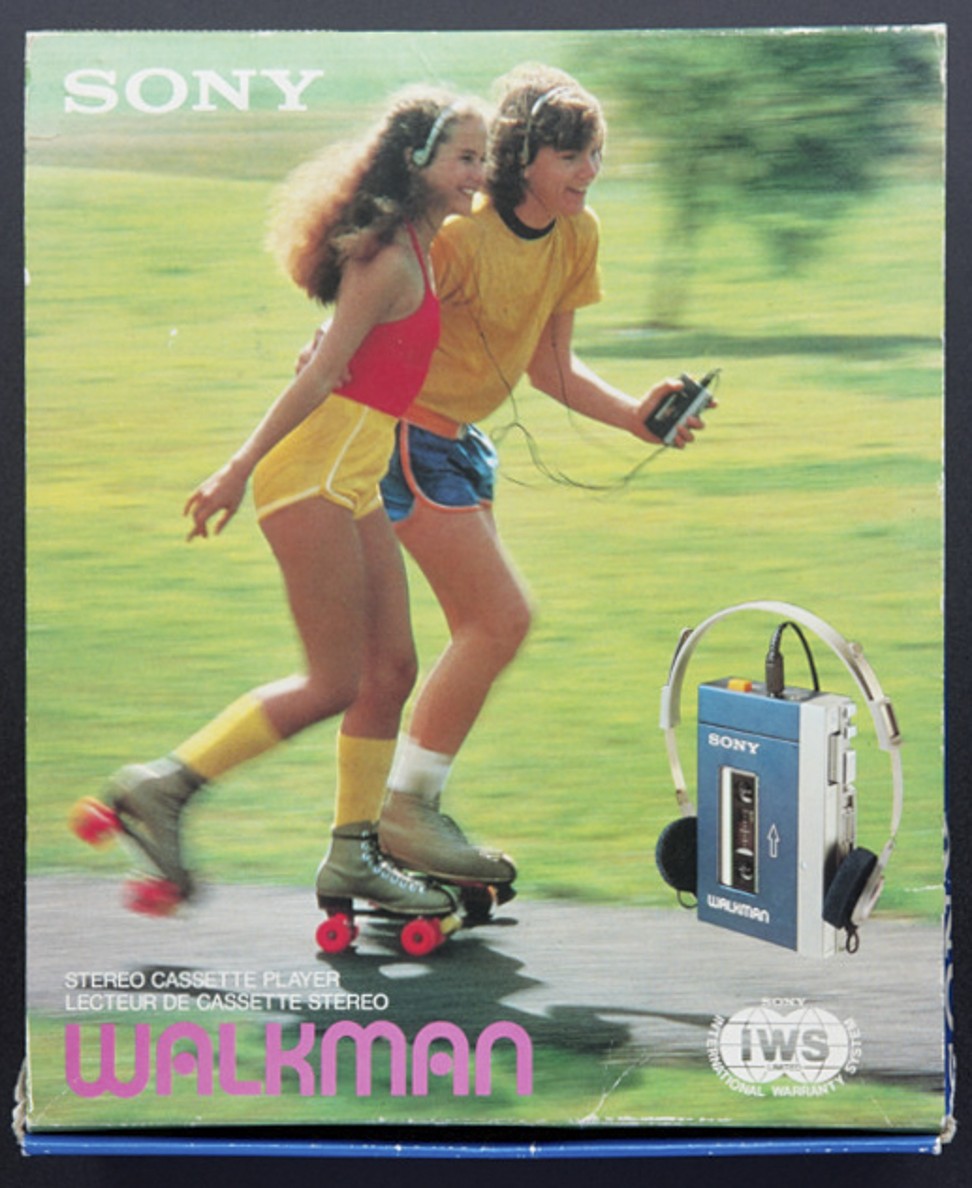

A 1979 advertisement for the Sony Walkman. Photo: Sony

More importantly, Paul Du Gay wrote in his book The Story of the Sony Walkman, it had “introduced the idea of ‘Japanese-ness’ into global culture, synonymous with miniaturisation and high-technology”.

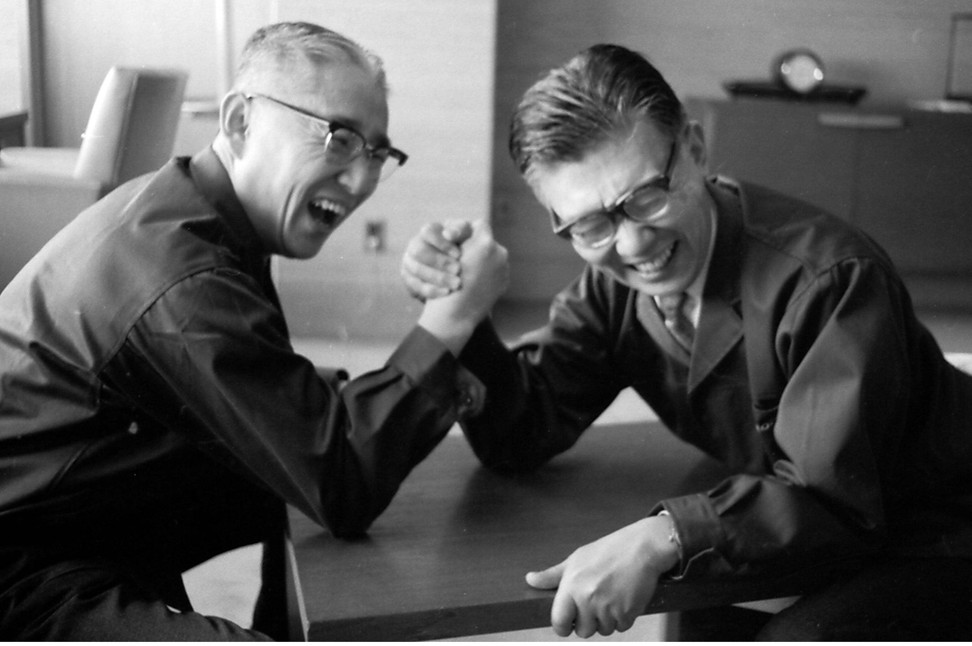

If the Walkman made Sony a household name around the world, the company’s story begins a good deal earlier. The firm can trace its roots to May 1946 – just nine months after Japan’s surrender at the end of World War II – when Masaru Ibuka opened an electronics repair outlet in a Tokyo department store. He was soon joined by Akio Morita, and the two men called their firm Tokyo Tsushin Kogyo, which translates as Tokyo Telecommunications Engineering Corp.

The Sony Walkman has been described as having introduced into global

culture the idea of ‘Japanese-ness’, one synonymous with miniaturisation

and high technology. Photo: Sony

It was not until 1958 that they decided to change the name to the more catchy Sony, which had echoes of the Latin word sonus, the root of sound and sonic, but was also close to the American term “sonny”, the tweaked Japanese phrase “sonny boy” having caught on in Occupation-era Japan as a term for a smart young man.

The fledgling firm’s main bank was not convinced by such an unconventional name, but Morita stood his ground. The company had produced Japan’s first tape recorder, the Type-G, and in 1955 unveiled the TR-55 transistor radio. It was so popular that within two years an updated version, the TR-63, became the first Sony product sold in the United States. Amusingly, the radio was slightly too large to fit into the chest pocket of a shirt, so the company gave its salesmen shirts with larger pockets so they could legitimately claim it was the world’s first pocket-sized transistor radio.

The product cracked the US market wide open and transistor radios became the must-have item for American teenagers the following decade. From selling 100,000 units nationwide in 1955, the industry was selling five million a year in 1968 – and a good proportion of them were Sony products.

Sony founders Akio Morita (left) and Masaru Ibuka. Photo: Sony

Encouraged by the popularity of its devices, Sony Corporation of America was set up in 1960 and the brand quickly helped to dispel the image of Japanese products as being of poor quality. That, in turn, enabled the company to keep its prices high.

The Walkman worked wonders for the brand around the world after its release in 1979, which also coincided with the launch by Sony of a life insurance firm, the company’s first foray outside its traditional field of electronics.

“While it is difficult for us to pinpoint specifically,” a company spokesman says, “maybe I could suggest that throughout our history, our success has been driven by the spirit of innovation that was instilled in the company by our founders and their belief in what others do not do.”

The early 1980s were a tough time for the electronics industry, however. Hit hard by a global recession, Sony’s star was said by some to be waning. Instead of retrenchment, new president Norio Ohga opted to forge ahead with the development of the revolutionary compact disc format and, in the early 1990s, the PlayStation, effectively launching the home game entertainment sector.

A Doom computer game played on a Sony Playstation. Photo: Getty

On December 4, 2019, Guinness World Records recognised the PlayStation as the world’s top-selling home video game console, having sold an incredible 450.19 million units over the space of 25 years. And it looks like the platform’s dominance is set to continue, with the next-generation PlayStation 5 due to be released in late 2020.

Not everything that Sony touched turned to gold, with Betamax arguably the biggest flop in the firm’s history.

The video-recording magnetic-tape format was unveiled in Japan in May 1975 and the first Betamax devices hit stores in the US six months later. The release unfortunately coincided with the launch of the rival VHS format by JVC – which had rejected an approach from Sony to get behind the Betamax brand. The upshot was what became known as the “format war” between the two companies.

Even though Betamax was seen to deliver better picture quality, consumers gradually opted for VHS because the players were cheaper and could record for 120 minutes, as opposed to 60 minutes for the Sony version.

The Sony Playstation logo at the Tokyo Game SHow in Makuhari, Chiba Prefecture in September.

Photo: AFP

Sales of Betamax machines dwindled and VHS emerged as the winner of the format war, although Sony only discontinued production of its recorder in 2002, and continued to produce Betamax cassettes until March 2016.

Back in the 1980s, Sony also went on an extensive spending spree, buying up companies in related industries in an effort to create “convergence” between consumer electronics, music, film, electronic gaming and the emerging internet. Those purchases included CBS Records, later renamed Sony Music Entertainment, in 1988 and Columbia Pictures, for a cool US$3.4 billion, the following year.

Not all its deals had happy endings, however, and the resulting bad press dented the brand name. To put the firm back on track, Sony broke with tradition in 2005 by appointing Howard Stringer as its chief executive. It was the first time a foreigner had overseen the management of a major Japanese electronics corporation.

The Sony CDP-101, the world’s first commercially released compact disc player. Photo: Sony

Welsh-born Stringer had moved to the US in the mid-1960s and joined broadcaster CBS before being drafted to serve in the US military in the Vietnam war. After completing his 10-month tour, he returned to CBS and stayed for the next 30 years. He rose to the post of president in 1988, three years after becoming a naturalised US citizen. Stringer left in 1995 to set up TELE-TV, a media and technology company.

In an effort to halt Sony’s slide, Stringer slashed about 9,000 jobs, sold businesses that were not considered core to its fundamentals, and encouraged closer cooperation between the different firms under the Sony umbrella. Stringer was also credited with advancing the movie arm of the company, producing a number of hit titles including the hugely successful Spider-Man franchise.

Yet while the old Sony imagination was still evident, new products often failed to take off. Aibo, for example – a robot dog that took its first, slightly jerky, steps in May 1999 – never really caught the public’s imagination. It was quietly discontinued in early 2006.

Howard Stringer, former Chairman and CEO of Sony Corporation, in September, 2005. Photo: AFP

Seven years after his appointment, Stringer had not been able to halt entirely Sony’s slide, and was replaced in 2012 by Kazuo Hirai. There was a sense that an “outsider”, a non-Japanese, had been unable to get to grips with elements of Sony’s Japanese corporate culture and had been hampered by language barriers.

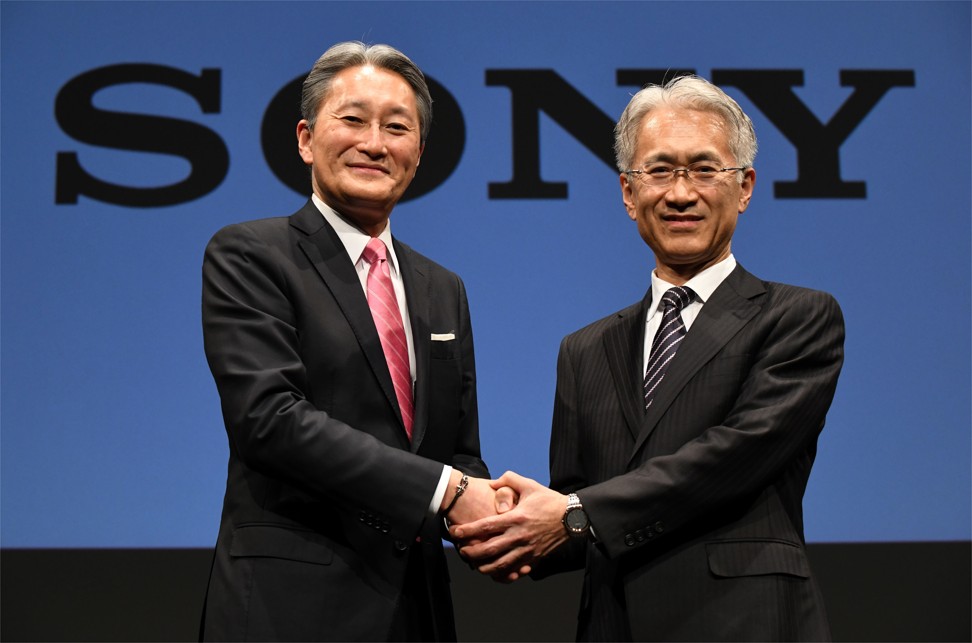

Hirai quickly put into practice his “One Sony” initiative to turn the company around, focusing on the firm’s traditional electronics business, an emphasis on gaming and mobile technology, and reducing losses in its television segment.

Over the next few years, a number of divisions were sold – notably its Vaio personal computer division – and 20 stores were closed in mid-2014.

A 30-year veteran of the company, Kenichiro Yoshida took over as CEO in early 2018 and quickly raised eyebrows by criticising his predecessor for failing to change as the electronics industry evolved. He ordered widespread restructuring – comparing it to “emergency surgery” – and insisted there would be no “sacred cows” within the company.

Kazuo Hirai (left) was succeeded as Sony President and CEO by Kenichiro Yoshida (right) in 2018.

Photo: AFP

In the financial year to March 2019, Sony posted record profits for a second consecutive year, thanks in good part to the roll-out of PlayStation Network, the network service for the gaming unit, and an upgrade of image sensors used in digital cameras and mobile phones.

The company also reported annual sales of 8.7 trillion yen (US$79.9 billion) and kept investors happy with a more than 27 per cent return on equity.

While the company spokesman declined to provide details of future product plans, he reiterated that Sony’s purpose was still to “fill the world with emotion, through the power of creativity and technology”.

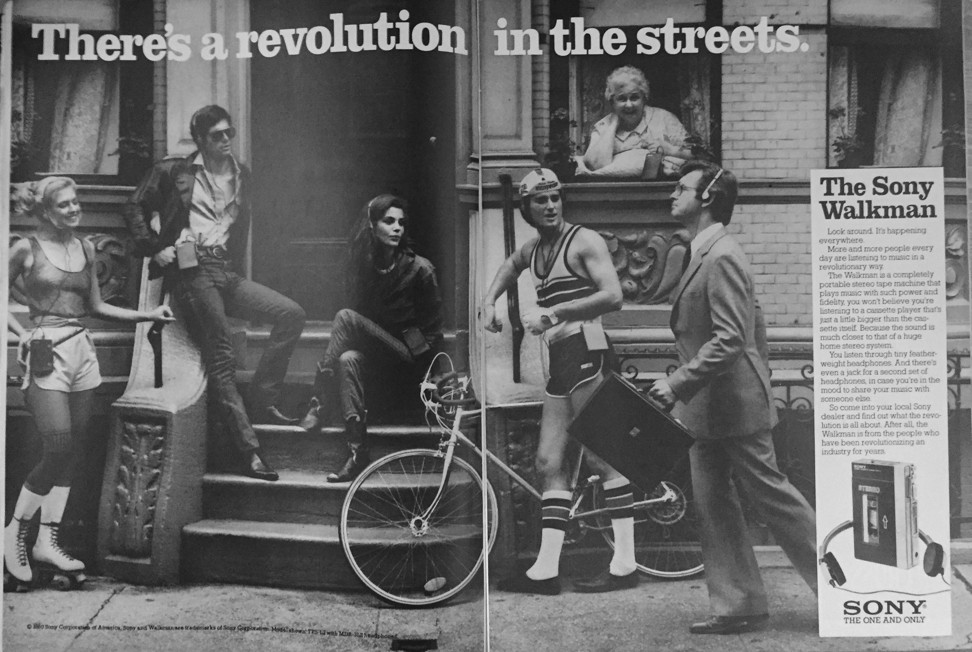

A 1981 ad for the Sony Walkman. It’s been a while since the Japanese company made a product

that has turned heads in the same way. Photo: Sony

Sony has clearly banished the concerns of a decade ago, is back on an even keel, and is exploring new opportunities. As it prepares to mark its 75th anniversary, however, it has been a while since Sony introduced a product that really turned heads.

The competition may be tougher than ever and the challenges ever growing, but it’s hard not to wonder what it would be like if Sony again broke the mould with a product that caught the imagination in the same way as a transistor radio once did. Or the Walkman that made Malia Verniolle dream.