Why are TikTok creators so good at making people buy things? – BBC

|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

SOURCE: Meredith Turits | BBC

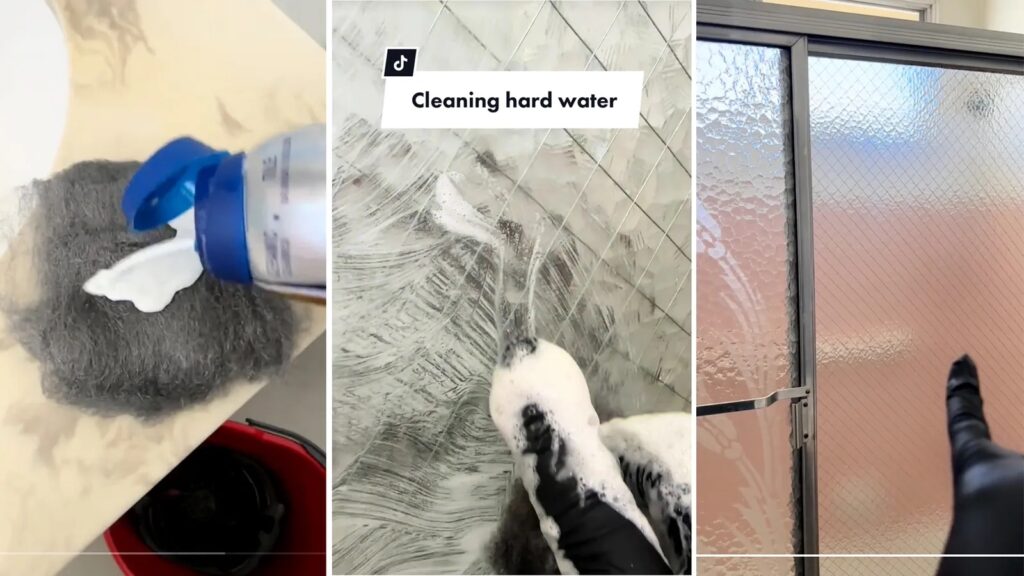

TikTok may not be the first place that comes to mind to find the best cleaning supplies. Yet #cleantok is alive and well – as is #dogtok, #beautytok and others. Increasingly, consumers are turning to social media to discover products, spending money based on the recommendations of both high-profile influencers and casual creators alike.

On #booktok, for example, creators share their book reviews and recommendations. Data shows users who promote certain books with the hashtag have driven sales of the titles they feature. The popularity of #booktok has also inspired devoted displays at major multinational book retailers; changed the way cover designers and marketers are approaching new titles; and this summer, even spurred a new publishing imprint from TikTok parent company ByteDance.

Yet there’s more than a user’s good endorsement that drives the instinct to purchase, say experts. A delicate psychological relationship with the face on the screen as well as the underlying mechanisms of TikTok both play major roles in moving users to buy something they see in their feeds.

Source credibility

“Video-based platforms like TikTok and Instagram have tremendously changed the way that we consumers make our purchasing decisions,” says Valeria Penttinen, assistant professor in marketing at Northen Illinois University, US. Crucially, these platforms offer users unprecedented exposure to products and services as they consume large volumes of content in such short spans of time.

There are a few elements that move users to hop onto creators’ endorsements. At the core of this, say experts, is “source credibility”.

People are likely to be moved to buy the products on screen if they perceive a creator as competent and credible. Users look to creators to “have a fit with the product or service” as a badge of authenticity, says Angeline Scheinbaum, associate professor of marketing at Clemson University’s Wilbur O and Ann Powers College of Business, in South Carolina, US.

Kate Lindsay, a journalist who covers internet culture, gives the example of a stay at home mum using a cleaning product. “They’re going to have a following of really like-minded people. When that person who looks like you says they’re a mom, they’re tired and this cleaning solution helps [them] get through the day … there’s a level of connection and trust where you’re like, ‘you look like me and this helpful for you, so it’ll be helpful for me’.”

A creator’s source credibility skyrockets when their recommendation is organic – an unpaid endorsement. “Organic influencers are so much more authentic … their motivation is to genuinely share a good or a service that has brought them joy or convenience in their life,” says Scheinbaum. “They sincerely want to share that with others.”

This authenticity can be especially powerful to drive purchases in niche categories, as creators are often deeply passionate and project specific expertise in areas few have claimed. “With these micro-influencers, the consumer is able to feel more confident that they’re buying from someone [who] uses that product … they have a little bit more of an emotional relationship”, says Scheinbaum.

Video posts also tend to increase credibility with viewers, more than still images or text. Penttinen says video creates a specific environment of “personal disclosure” that draws in users: even small elements like being able to see a creator’s face, hands or hear the way they speak can make a user view them as more trustworthy. Indeed, research has shown YouTube influencers infuse their reviews with personal information to appear more like a close friend or family member – and the more a viewer feels they “know” the creator, the more they trust them.

Scheinbaum adds that posts with both action and verbal cues – especially the demonstrations and transformations in TikTok videos, which almost serve as 30-to-60 second micro-infomercials – can inspire “particularly effective persuasion”.

The parasocial effect

One of largest elements that inspires consumers to purchase is an emotional connection to these creators.

This phenomenon, called a parasocial relationship, leads audience members to believe they have a close association or even a friendship with a personality, when the relationship is actually one-sided – often, the content creator may not know the viewer even exists. These nonreciprocal relationships manifest often in social media, particularly with influencers and celebrities, especially the more users are exposed to their content.

The phenomenon plays a role in consumer behaviour, too. “Parasocial relationships are so strong that people are moved to buy,” says Scheinbaum, both in terms of influencers pushing sponsored products and organic creators sharing their favorite personal items.

When you continue to fall more and more in love with these people, it stokes the fear of not capitalising on that relationship, or showing your devotion to that relationship.

–

Valeria Penttinen

Penttinen explains that as consumers begin to know a creator’s preferences and values, and watch them disclose personal information, they start to treat their recommendations the same way they would their own real-life friends. She adds these parasocial relationships often drive users to make repeat purchases, especially on TikTok; the platform’s algorithm feeds users content from the same accounts often, and repeated exposure can contribute to the one-sided relationship.

She adds parasocial relationships on TikTok can also drive a fear of missing out, which spurs buying behaviour: “When you continue to fall more and more in love with these people, it stokes the fear of not capitalising on that relationship, or showing your devotion to that relationship.”

Perfectly packaged

Lindsay says TikTok also has a kind of spirit to its product-centric content that users can find especially compelling.

“TikTok has this way of making shopping like a game in a sense, because everything ends up almost being packaged as part of an aesthetic,” she says. “You’re not just buying a product, you’re buying something in pursuit of this larger lifestyle.” It can draw the user into wanting to be part of these trends or get in the discourse, which can include trying out a product.

She adds that particular genres of TikTok content can be highly persuasive: she points to examples like “things you didn’t know you needed”, “holy grails” or “things that saved my…”. “There’s a little bit of surprise and delight when you’re just scrolling and then you see this thing you didn’t know you needed or didn’t know existed,” says Lindsay.

Crucially, she says, the short-form intimate nature of TikTok videos makes recommendations feel more natural, and opens up a pathway for users to trust creators. In contrast to the shiny influencers of Instagram, the less polished the content, the more she believes consumers feel like they’re making their own decisions to purchase from recommendations – “unpacking it in their own brain”.

Buyer beware

Yet consumers can often find themselves wrapped up in these emotional purchases to their detriment, says Scheinbaum, who is also the author of The Dark Side of Social Media: A Consumer Psychology Perspective.

In some cases, the parasocial effect and subsequent intimacy that social media evokes can be so strong that users don’t stop to “sleuth” whether the endorsement is sponsored or not, she says.

Particularly, younger users or less savvy consumers may not know the difference between an advert and an organic recommendation. Even users in a hurry could be vulnerable, she says. The nature of TikTok’s rapid, quick clips may also make adverts harder to spot, believes Linsday.

Additionally, these emotional attachments that drive purchases may make people likely to overspend, says Penttinen. On TikTok, many of the products users talk about aren’t expensive, which can make purchasing feel lower stakes. That can be a problem, she adds, because what one creator might find good for them isn’t necessarily good for the user – you might not like that novel you bought because it’s been all over #booktok, after all.

Consumers shouldn’t feel they have to scrutinise every purchase they make off TikTok, but experts say it’s important to know why the platform can inspire users to spend money – especially before they hit the check-out.

This article was originally published on BBC. You can view the original article here.